Cell-phone Frequencies

In the dark ages before cell phones, people who really needed mobile-communications ability installed radio telephones in their cars. In the radio-telephone system, there was one central antenna tower per city, and perhaps 25 channels available on that tower. This central antenna meant that the phone in your car needed a powerful transmitter — big enough to transmit 40 or 50 miles (about 70 km). It also meant that not many people could use radio telephones — there just were not enough channels.

The genius of the cellular system is the division of a city into small cells. This allows extensive frequency reuse across a city, so that millions of people can use cell phones simultaneously.

A good way to understand the sophistication of a cell phone is to compare it to a CB radio or a walkie-talkie.

- Full-duplex vs. half-duplex – Both walkie-talkies and CB radios are half-duplex devices. That is, two people communicating on a CB radio use the same frequency, so only one person can talk at a time. A cell phone is a full-duplex device. That means that you use one frequency for talking and a second, separate frequency for listening. Both people on the call can talk at once.

- Channels – A walkie-talkie typically has one channel, and a CB radio has 40 channels. A typical cell phone can communicate on 1,664 channels or more!

- Range – A walkie-talkie can transmit about 1 mile (1.6 km) using a 0.25-watt transmitter. A CB radio, because it has much higher power, can transmit about 5 miles (8 km) using a 5-watt transmitter. Cell phones operate within cells, and they can switch cells as they move around. Cells give cell phones incredible range. Someone using a cell phone can drive hundreds of miles and maintain a conversation the entire time because of the cellular approach.

In a typical analog cell-phone system in the United States, the cell-phone carrier receives about 800 frequencies to use across the city. The carrier chops up the city into cells. Each cell is typically sized at about 10 square miles (26 square kilometers). Cells are normally thought of as hexagons on a big hexagonal grid, like this:

Because cell phones and base stations use low-power transmitters, the same frequencies can be reused in non-adjacent cells. The two purple cells can reuse the same frequencies.

Each cell has a base station that consists of a tower and a small building containing the radio equipment. We’ll get into base stations later. First, let’s examine the “cells” that make up a cellular system.

Cell-phone Channels

A single cell in an analog cell-phone system uses one-seventh of the available duplex voice channels. That is, each cell (of the seven on a hexagonal grid) is using one-seventh of the available channels so it has a unique set of frequencies and there are no collisions:

- A cell-phone carrier typically gets 832 radio frequencies to use in a city.

- Each cell phone uses two frequencies per call — a duplex channel — so there are typically 395 voice channels per carrier. (The other 42 frequencies are used for control channels — more on this later.)

Therefore, each cell has about 56 voice channels available. In other words, in any cell, 56 people can be talking on their cell phone at one time. Analog cellular systems are considered first-generation mobile technology, or 1G. With digital transmission methods (2G), the number of available channels increases. For example, a TDMA-based digital system (more on TDMA later) can carry three times as many calls as an analog system, so each cell has about 168 channels available.

Cell phones have low-power transmitters in them. Many cell phones have two signal strengths: 0.6 watts and 3 watts (for comparison, most CB radios transmit at 4 watts). The base station is also transmitting at low power. Low-power transmitters have two advantages:

- The transmissions of a base station and the phones within its cell do not make it very far outside that cell. Therefore, in the figure above, both of the purple cells can reuse the same 56 frequencies. The same frequencies can be reused extensively across the city.

- The power consumption of the cell phone, which is normally battery-operated, is relatively low. Low power means small batteries, and this is what has made handheld cellular phones possible.

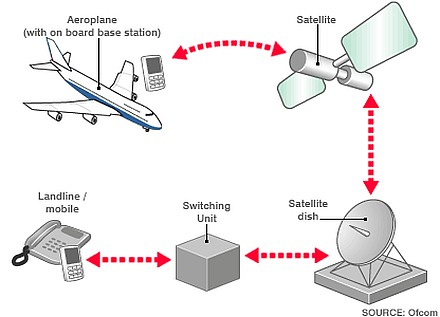

The cellular approach requires a large number of base stations in a city of any size. A typical large city can have hundreds of towers. But because so many people are using cell phones, costs remain low per user. Each carrier in each city also runs one central office called the Mobile Telephone Switching Office (MTSO). This office handles all of the phone connections to the normal land-based phone system, and controls all of the base stations in the region.

Cell-phone Codes

All cell phones have special codes associated with them. These codes are used to identify the phone, the phone’s owner and the service provider.

Let’s say you have a cell phone, you turn it on and someone tries to call you. Here is what happens to the call:

- When you first power up the phone, it listens for an SID (see sidebar) on the control channel. The control channel is a special frequency that the phone and base station use to talk to one another about things like call set-up and channel changing. If the phone cannot find any control channels to listen to, it knows it is out of range and displays a “no service” message.

- When it receives the SID, the phone compares it to the SID programmed into the phone. If the SIDs match, the phone knows that the cell it is communicating with is part of its home system.

- Along with the SID, the phone also transmits a registration request, and the MTSO keeps track of your phone’s location in a database — this way, the MTSO knows which cell you are in when it wants to ring your phone.

- The MTSO gets the call, and it tries to find you. It looks in its database to see which cell you are in.

- The MTSO picks a frequency pair that your phone will use in that cell to take the call.

- The MTSO communicates with your phone over the control channel to tell it which frequencies to use, and once your phone and the tower switch on those frequencies, the call is connected. Now, you are talking by two-way radio to a friend.

- As you move toward the edge of your cell, your cell’s base station notes that your signal strength is diminishing. Meanwhile, the base station in the cell you are moving toward (which is listening and measuring signal strength on all frequencies, not just its own one-seventh) sees your phone’s signal strength increasing. The two base stations coordinate with each other through the MTSO, and at some point, your phone gets a signal on a control channel telling it to change frequencies. This hand off switches your phone to the new cell.

For more Detail: How Cell Phones Work